Basic Research and Adaptive Management Projects

To protect Kauaʻi’s endangered and threatened forest bird species, KFBRP conducts basic research to fill information gaps regarding their ecology and applied research to determine which factors (e.g., food limitation, disease, predation) most strongly influence their declines. This information is critical to conservation planning and monitoring population responses to management efforts. Partnership with universities, agencies, and not-for-profit groups are essential to these efforts. Here, and described below, are some potential areas of collaboration; if you have another idea, please let us know. Our Project Coordinator, Dr. Lisa “Cali” Crampton, has affiliate status at several universities and can serve as a member of graduate committees.

Given the remote and rugged region inhabited by these species, detailed knowledge, their abundance, distribution, and population trends has been hard to procure. Recent work has focused on determining occupancy, habitat use, home range size, survival, nesting success, and movements of these species both in the core of their range and on the periphery (Behnke et al., 2016, Bonnette et al., 2017, Crampton et al. 2017, Fantle-Lepcyk et al. 2017, Hammond et al. 2015 and 2016, VanderWerf et al. 2014). Particularly disturbing is evidence of accelerating declines of the six honeycreeper species that inhabit the Plateau (Paxton et al. 2016). Concurrently, our research has documented increasing prevalence of mosquitoes and avian malaria on the Alakaʻi Plateau (Atkinson et al. 2014, Glad and Crampton 2015), modeled impacts of different management alternatives on puaiohi recovery (Fantle-Lepcyk et al 2018), and determined that non-native frugivores are unlikely to replace puaiohi’s seed dispersal services (Kaushik et al., 2018).

Current areas of interest include:

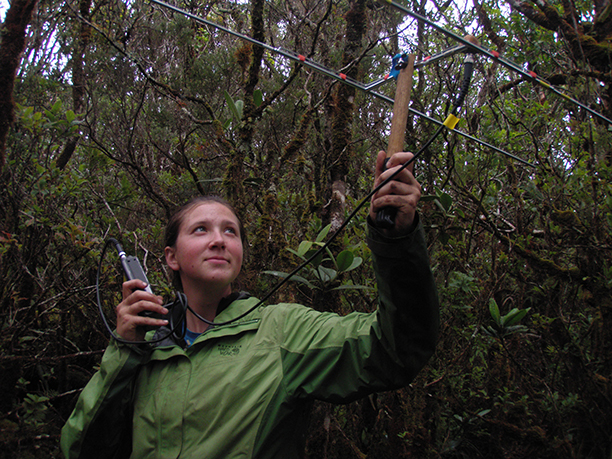

- Using technology (e.g., LiDAR (with CalPoly and UCLA), automated recording units (with American Bird Conservancy, National Fish And Wildlife Federation and UH Hilo), and automated telemetry networks (with USGS, Holohil and Club 300) to more easily document and investigate the species’ distribution and abundance at small and large spatial scales (see presentation). Future research in these areas include development of habitat suitability models for puaiohi and ʻiʻiwi, modeling suitable habitat for translocation, developing algorithms for sound recognition of honeycreeper species, and broader application of the telemetry network. We are also interested in determining the distribution of the more common forest birds (e.g., Kaua‘i ʻelepaio, ʻapapane) at elevations < 1000m.

- Continuing to collect baseline demographic, dietary, and disease prevalence data on forest birds by banding, sampling, and resighting birds. We examined the diet of ʻakikiki and ʻakekeʻe across their range, with a view to understanding how invasive species might affect diet and to informing conservation programs, such as conservation breeding (Costantini et al, 2024). In the future, these data will help assess impacts of management efforts (see below). We have a wealth of demographic data ripe for analysis, which could be used to analyze territorial dynamics, survival (e.g., as a function of disease status), habitat use, predictors of nest success.

- Conducting essential research on temporal and spatial distribution and movements of adult and larval mosquitos to inform landscape control of mosquitoes. Recently, we worked with USGS, USFWS and DOFAW to examine the annual cycle of mosquitoes in the core forest bird range; next year, we hope to assess the distribution of mosquitoes across the Plateau during peak months. Another area of interest is movements of mosquitoes between low elevation areas and the Plateau; we hypothesize that mosquito populations on the Plateau are “subsidized” by low elevation mosquitoes, as we have yet to find larval mosquitoes present year round on the Plateau.

- Improving the efficacy of our rodent control efforts using camera trapping to assess interaction between traps and animals while manipulating key variables, such as lure type and trap height (with DOFAW, American Bird Conservancy, and USFWS). We hope to find funding to continue and expand this work.

- Investigating the responses of forest birds to threat management, such as rodent control or ungulate fencing, in an adaptive management context. Suitable response metrics include survival, population level changes (e.g., occupancy, density), and nest success. From 2010-2012, we investigated changes in forest bird density before and after ungulate fencing at a limited scale on one control and one treatment plot (see presentation); as such fences proliferate on the plateau, there are yet more opportunities to expand this study. We also designed and deployed rat proof nest boxes with the goal of improving puaiohi nest success, but had to interrupt this study due to other more pressing issues. Currently, we are seeking funding to compare survival and occupancy of puaiohi on rat trapping grids vs. control plots.

- Understanding predator dynamics on the Plateau: what influences the variation of rat populations (and what they consume) in space and time? What impact does rat removal have on cat densities and diet? How much predation pressure do cats exert on forest birds? Again, we are seeking funding to answer this question.