How You Can Help Kauaʻi’s Forest Birds by Shopping on Black Friday / Cyber Monday

/in Blog/by MonikaDo you plan on ordering anything from Amazon this Holiday Season? If you answered yes to this question, and I am pretty sure you did, then you can help Kauaiʻs Forest Birds by just changing one little habit before you place your order.

Just remember to use this link to go to Amazon Smile, a portion of your purchase will will be returned to KFBRP for valuable research and conservation. WOW! How easy is that? Shop on Amazon to buy Christmas gifts, and Kauaʻi’s forest birds benefit. Pretty easy right? Just make sure to bookmark the link.

What are you waiting for?

Did you know that you can also buy our books on Amazon? Not only are the proceeds returned to KFBRP, but your kids, your friendsʻ kids, and your kidsʻ teachers can get a great book that teaches them about Kauaʻi’s forest Birds.

KFBRP has two childrenʻs books available for purchase:

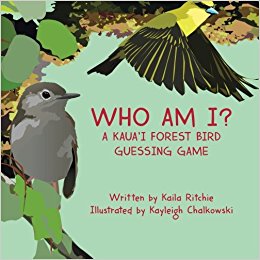

Who Am I? A Kauaʻi Forest Bird Guessing Game

This book introduces Kauaʻiʻs forest birds with a fun rhyming poem and then invites children to guess which bird is described.

and

He Moʻolelo Pokole

He Moʻolelo Pokole

This book is a short story about the plight of Kauaʻiʻs forest birds written in both English and Hawaiian.

Of course, if you really want to make a difference for these birds, just click on the donate button to the right.

HAPPY HOLIDAYS from KFBRP!

124 A24s – Weapons to Fight Rats

/in Blog/by MonikaEarly October, everyone’s favorite time when the leaves start to change and all of our food and drinks contain pumpkin spice. Here on Kaua’i, we were pulling out our down jackets not to go pumpkin picking, but to venture out to our high elevation field camp on the Alaka’i Plateau. After the success we’ve had in decreasing rat numbers with the 300 self-resetting A24 rat traps that we deployed in 2015 and 2016, we felt it was important to deploy a new grid in well-established Puaiohi territories. Our research shows that nesting Puaiohi females are very susceptible to rat predation.

We’ve been in the planning stages for this new grid for several months now to find the ideal area in which to protect the most Puaiohi from rat predation. We ran habitat suitability models based on high resolution LiDAR data, looked at previous nest locations and detections, and focused on topography to see we could even access some of these areas. After all this careful planning, it was finally time to get these 124 new A24 rat traps out into the field to start protecting endangered forest birds. Our timing is good; the breeding season for Puaiohi starts in the late winter, allowing the traps to sit out all fall removing rats that could predate the birds on their nests. It is also the first time KFBRP has ever collected rat presence/absence data during fall months, leading to a more complete understanding of these invasive predators.

While hiking into camp on October 7th I was excited to see the birds again – I think so often about them, but so rarely get to spend time with them. Schlepping the heavy pack full of drills, rat traps, CO2 cartridges, and more paid off on the very first day as I was startled by a Puaiohi call while deploying a trap. I look up and a juvenile is sitting on a branch a few feet from me. Feeling fulfilled as I finish arming the trap, I now know that not only does it have the potential to save birds, but rat removal has implications for several trophic levels. A recent study on the Big Island found that “invasive rats indirectly alter the feeding behavior of native birds.” In the presence of rats, the birds foraged for insects and fruits higher in the canopy, using less of the available vertical foraging space. This change could be due to avoidance behavior by the birds or that the rats sufficiently deplete arthropod and fruit closer to ground level. The good news is that birds also responded to the removal of the invasive predators with behavioral plasticity, not just their presence. This gives me hope that our hard work can restore balance to the remaining habitat of the forest birds.

Leaving the field knowing we met our goal of deploying over 100 rat traps was gratifying, however I know we have a lot of work ahead of us to save the Puaiohi. I am restless, as I am sure the rest of the team is, to get back out the grid and hopefully see lots of dead rats and live native forest birds. These birds are facing some pretty big challenges – climate change, disease, habitat loss – and we are all happy to remove one big threat to their success.

Hurricane Hell

/in Blog/by MonikaFrom the diary of Justin Hite, KFBRP Field Supervisor

I hope it is not too insensitive to ponder Hurricane Season in Hawai’i while the effects of Hurricane Florence are still unfolding in North Carolina. But from the perspective of a honeycreeper-lover like myself, this has been a stressful chaotic season. Hector thundered monstrously by to the south. Lane caused widespread panic and preparations as it stalled and banked and dumped absurd amounts of rain, but then mostly slipped by without a knockout punch. Two hundred-mile wide Olivia is losing steam but on course to slam directly into Maui. As I write this it is only 200 miles away from landfall. Each time a hurricane looms, crews must be pulled off their conservation efforts in the field over concerns for their safety, and our efforts are redirected to securing human lives and property instead. Countless conservation hours are diverted to shutting down and reopening our office.

Meanwhile the last few hundred ‘Akikiki, many of which are currently upside down on an ‘Ohia branch and tearing a small caterpillar out from under a cluster of lichen, are presumably oblivious to the potential threats they faced this summer. Hurricanes Iwa (1982) and Iniki (1992) devastated Kaua’i’s native forest birds, speeding along the extinction of three species, Kama’o, Kauai O’o and the O’u. What would have happened if we’d received a direct hit from Hector or Lane? What if Olivia had tracked further north and came directly at Kaua’i? What will Olivia actually do to Maui’s two critically endangered birds, the Akohekohe and Kiwikiu?

Hurricanes are a natural part of the Hawaiian ecosystem. Honeycreepers have been here for upwards of 5 million years, and have dealt with countless hurricanes. But staring down a gigantic storm is one thing when you are standing tall and proud and healthy. When your population is at a tiny fraction of its former strength, when you are isolated on a patch of habitat on Kaua’i 1% of its former size, it doesn’t look as good. Unfortunately, hurricanes are expected to become more frequent and more severe under most climate change scenarios.

We may be “one good hurricane away” from losing several of our native birds. May that storm never hit. Though, of course, some day it will. Damn!

A Thank You Letter from a Helicopter Pilot

/in Blog/by Monika Did you know that much of the conservation work that takes place on Kauai would be impossible without helicopters?

Did you know that much of the conservation work that takes place on Kauai would be impossible without helicopters?

The remote rugged terrain restricts the amount of gear than can be packed in. Conservationists like those that work for the Kauai Forest Bird Recovery Project need gear, food, and supplies to complete their work. They must hike for many miles along steep, uneven, and unmarked trails to get to field camps and conservation areas. It would be nearly impossible to get all the scientists and their gear to these locations without helicopters. While we often thank our pilot for delivery and return, it was quite a treat to get a thank you from this helicopter pilot who makes our work possible.

If you want to learn more about the use of helicopters in conservation, check out this presentation on using helicopters for conservation on Kauai.

A Thank You Letter

I’m a helicopter pilot who flies the various conservation crews all over the island of Kauai. I get a lot of “thank you-s” while flying this rugged group about the island. When dropping them off at their remote campsites so they can get to the work they are so passionate about, I hear, “Thanks for lift!” When extracting these crews, after they have been clawing through the mud, sleeping in wet tents, and living off cold cans of Spaghetti O’s, I hear, “Thanks for getting us out of the field.” My reply to their gratitude is always the same, “My pleasure, I have the easiest job out of any of you guys”.

The flying may be easier and more comfortable than working and camping in the wettest places on the planet, but it is by no means easy flying. I may have cut my teeth in other types of heli ops, but flying conservation in Hawaii has sharpened them to a fine point. It’s experiences such as tow-in landings over 1000 foot waterfalls while certain botanists climb the exposed skids to safety. It seems evolution would see to it that rare plants only grow in places even helicopters have trouble getting to. Also, situations like slinging ungulate-proof fences high atop the ridges of the Napali Coast, where it’s either windy or really dam windy. And then, there’s the weather, the ever dynamic weather. The visibility can change just as fast as the wind blows, which leaves little time for mistakes. This is by far the most challenging part of my job. But even when the weather takes a turn for the worse, and we have to leave crews in the field, I still hear “Thank you for trying.”

Despite all the hair raising challenges I face while flying conservation crews around, it is my favorite part of the job. I’m honored to be a part of this hearty group of people who are well educated, well informed, and so passionate about the work they do. These crews are literally knee deep in protecting our native forests and animals. They give their sweat and blood for the cause. After a tough week in the field, I listen to the trials and tribulations these crews face. Sometimes I’ll say, “Well, that’s why you guys get the big bucks.” One soldier of conservation replied to that quip with, “Ya right, we get paid in sunrises and sunsets.” And that is absolutely true. You are rich. Rich in experiences in nature, and rich in seeing sites so few are ever graced with, and rich with doing work that fulfills the soul.

So with that, it’s my turn to say “Thank you.” Thank you for hiking miles and miles to collect rare seeds. Thank you for diving head first into shearwater burrows to check on the chicks. Thank you for pounding fence posts until your hands bleed. Thank you for climbing 40-foot extension ladders suspended only by ropes to ever so gently collect endangered forest bird eggs. Thank you for the fence checks, the cat hunting, the bird strike counting, the weeding of invasives and the protection of the natives. Thank you for finding work you are passionate about and sticking with it, even in the sometimes harsh conditions of the native Hawaiian forests.

I’m sure that if the citizens of Hawaii could share my birds eye view, and see what happens out there on the front lines of conservation, they would share my respect and gratitude for these crews. I hope to continue to help out with this ever so important cause. And, as long as the weather cooperates, I’ll try to get you home in time for happy hour.

Sincerely. Chris Currier. Airborne Aviation

staff

staff